Jul 30, 2013

Solo Improv on UtahImprov.com

"You come up against any weaknesses you have - big time!" - Andy Eninger

There's a great article on solo improv on the UtahImprov.com by Jesse Parent called Solo Improv: The Art of Playing with Yourself. I think it was posted in August of 2002. I took the same workshop Parent refers to with Andy Eninger. I find Eninger a wonderful inspiration. He was kind of the pioneer that led the way for a lot of us solo improvisers that are performing nowadays (like myself and Jill Bernard).

In the article, Eninger is quoted again while referring to how in solo improv the luxury of time is a beneficial tool, since it can "allow the improviser to explore themselves, reveal personal themes, thoughts and beliefs"

I sure hope so. I'm doing a long solo set on September 1st.

In the article, Eninger is quoted again while referring to how in solo improv the luxury of time is a beneficial tool, since it can "allow the improviser to explore themselves, reveal personal themes, thoughts and beliefs"

I sure hope so. I'm doing a long solo set on September 1st.

This kind of stuff is percolating in my mind recently...

Jul 27, 2013

Photos from IFO5

|

Jul 24, 2013

Measuring Sticks and Process Glimpses

|

| Chef as entrepreneur... sharing, teaching, selling. |

"Sure, I want everyone to hear my album; I want everyone to love it. But the number of people listening actually makes no difference to my life, my art, or my ability to create more art.Musician Kim Boekbinder has launched an interesting project. She has created an album with outer space as the theme and to ramp up for getting it out into the world, she has made a new persona and a new website: Impossible Girl.

Her first post involves a rumination about numbers. Her thoughts remind me of my own post from a few weeks ago about developing audiences. She explains how after raising $35,000 via a Kickstarter campaign for her album, she still couldn't get it into the big leagues...

"My album actually cost me over $50,000, partly because I was working for a wider release. My goal was to have more than a DIY crowd-funded success. I wanted to do a traditional album launch. To leverage myself to a level where I don’t have to crowd-fund every single release. I worked hard, made gorgeous videos, paid for photo shoots, hired a fancy/expensive NYC PR firm, did interviews. I wrote to bloggers, journalists, scientists, musicians, labels, radio stations, managers, booking agents, and more. I played at SXSW. I had a big fancy album release show at Joe’s Pub. I ticked all the boxes I could. But most of all, I made an amazing album. I gave it everything I had. And more.

My album isn’t selling now - a failure by industry standards. But my album did sell, it was pre-funded by a large group of trusting people who are now incredibly happy with the music. I dreamed of a wider release, but who really cares?

Her new plan is to start "a monthly subscription pass to my creative process..." (You can currently join for $2/month).

First off, I think Kim's music is awesome an she is a super-savvy internet-age entrepreneur as far as getting her work out to folks and raising money. She also hangs with a similar crowd (i.e. Molly Crabapple, Amanda Palmer, etc.). That said, her recent post raises some thoughts and concerns for me.

She offers a good cautionary tale on measuring success by outside parameters. She admits...

"I keep trying to re-create a version of success defined by huge investments for huge returns. Gambling really. And while I “gambled" on this album what is a huge sum of money for me, I just can’t compete with the numbers the industry throws at things. I don’t have access to any of the traditional tools, but I’m still using their measuring stick.

I believe this is an incredibly astute observation. Of course you are not going to reach "success" if your yardstick is the same as selling as many albums as Brittany Spears or Eminem. That's just not the sandbox Kim plays in. I relate with this. I have come to embrace the niche market of the Long Tail. I don't want to reach "as many people as possible." I want to reach those specific folks that will like and support my work and through it, me. It is a sniper rifle approach instead of a shotgun approach.

The other thing that sticks out to me is her plan to charge people a glimpse inside her creative process with a subscription service. While at first glance, this seems harmless enough, I think there is a horse-before-the-cart thing going on here.

Sure, fans (.i.e people who are already really into her work) may subscribe. But if you come in new to Kim's work, I'm not sure how many will pay for the privilege of seeing how the song creation happens. I think the sharing of the process can be used to draw potential patrons in. They can get to know your thoughts, processes and working methods. This gives a foundation for appreciating your work. It also acts as a carrot to tempt people towards the final product.

Artist/Writer Austin Kleon equates it with cooking show hosts like Martha Stewart, Emeril Lagasse or Rachel Rey. They teach and share on their shows (read: blog for this analogy) and then sell the actual final products (i.e. linens, kitchen ware, cookbooks, etc.) to their developing fanbase.

Jason Fried of 37 Signals (the inspiration for Kleon) has a great talk on this... HERE (about at the 14.30 minute mark). He claims that chefs are the best business entrepreneurs, because they know that sharing leads to more sales. He suggests that businesses emulate famous chefs.

I would add that individual artists, non-profits or performance groups do the same. Imagine an improv troupe with a blog or website that posts little snippets of rehearsals, video travel logs about their trips to festivals and silly/interesting interviews with cast members. The improv group could shoot short improvised videos, record an improvised podcast or teach workshops or classes. The actual improv shows are the real performance (the product), but they generate anticipation and community by giving away a glimpse into the process and by sharing the extra bits beyond simply the shows.

I would add that individual artists, non-profits or performance groups do the same. Imagine an improv troupe with a blog or website that posts little snippets of rehearsals, video travel logs about their trips to festivals and silly/interesting interviews with cast members. The improv group could shoot short improvised videos, record an improvised podcast or teach workshops or classes. The actual improv shows are the real performance (the product), but they generate anticipation and community by giving away a glimpse into the process and by sharing the extra bits beyond simply the shows.

I guess the fact Kim is doing a subscription is not what bothers me. It bothers me that, by charging, she is making it a barrier to getting to know her process and, by extension, her. This is totally her call, though, and even though it is not the way I would do it, I applaud her continued efforts to get her album out into the world and support herself as an artist.

Read Kim's original post HERE.

UPDATE [ June 2013] - Kim seems to still be sharing openly with a bit here and there on her Tumblr. Her subscription service is still going. It is called Mission Control. It is now $5/month (minimum).

Jul 22, 2013

Jul 21, 2013

Comportment Counts

|

| Mr. Samuel Beckett was a gentleman |

There were many other aspects to developing audiences that the conversation made me think about that I did not touch on in that post. As corollary to that post, I wanted to say a few words about behaving nicely and how this can affect audience development.

I believe audiences are affected, especially in regards to growth and retention, by the deportment of the artist. How one behaves in daily life to others, including prospective audience members, really does affect how the work is perceived on stage.

It is similar to the Girl-On-Stage theory. The Girl-On-Stage is a pet theory I have developed to describe the sensation of being seriously drawn, beguiled or attracted to a character one sees onstage only to later find out, in the harsh light of real life, that the actor that portrayed her is absolutely nothing like that.

Irrationally, perhaps, it is often a let-down...

I know several actors who are very skilled and, in some instances, absolutely amazing to watch onstage. But in daily life they are rather deplorable. Sometimes it is insecurity (hard to believe, but insecurity is a big driving force behind many dramatic artists getting into the theatre to begin with) or maybe social awkwardness. But most of the time, the actor is just plain rude. A total jerk...

I wonder if they would have quite the same reputation in the press and amongst their fan base if audiences and critics observed them behaving so indiscreetly and inconsiderately in real life.

Over the years I have had the privilege on several occassions to personally meet artists whose work I first discovered and then admired from afar. What has struck me most often is how they came off when not on the stage. Sometimes they turned out to be quite gentlemanly. They conducted themselves in public–as in meeting strangers like myself–with consideration, amiability, and open-mindedness.

Of course, I have also had the opposite experience. Meeting artists whose work I’ve admired, then discovering them to be personally arrogant, crude, and discourteous. This is sometimes a surprising turn, especially since their work on stage is often sensitive and graceful. I remember meeting one rather well-known monologuist, powerful and artful on stage, in person and he turned out to be quite dismissive and stand-offish.

Sometimes, when I return to their work later after these personal interactions, I’ve found it to be more flawed, more uneven than before–testimony, perhaps, to the presence of the artist, or the person, in the art. Maybe I'm just subconsciously on the look-out for things to bring the work of unpleasant people down a few pegs.

And I think this urge is at the root of how personal behavior affects an artist's relationship with his or her audiences. Patrons, I believe, like to relate with the artist just as much, if not more so, than to the art itself. We are social creatures. I always feel closer to the art if I feel I know something about the artists. And if I like the artist involved, I root for the art. I am more receptive. If I do not like the artist, I usually don't even bother with the art. In these instances, the artist has become his or her own gate-keeper and has barred the way for me as a potential patron.

One of the playwrights of history I admire a great deal is Irishman Samuel Beckett. There is an infamous anecdote about the writer of Waiting for Godot while he was living in Paris in early 1938. While refusing the solicitations of a notorious pimp, who ironically went by the name of Prudent, Beckett was stabbed in the chest and nearly died. James Joyce arranged a private room for the injured Beckett at the hospital. The publicity surrounding the stabbing attracted the attention of Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, who knew Beckett slightly from his first stay in Paris; this time, however, the two would begin a lifelong companionship culminating in marriage. At a preliminary hearing, Beckett asked his attacker for the motive behind the stabbing. Prudent casually replied, “Je ne sais pas, Monsieur. Je m’excuse” (“I do not know, sir. I’m sorry”). Beckett occasionally recounted the incident in jest, and eventually dropped the charges against his attacker—partially to avoid further formalities, but also, and this is the part I find so wonderful, because he found Prudent to be personally likeable and well-mannered.

When he became more and more famous, Beckett rarely granted interviews. He did not chase the press and, really, to a large extent ignored it. He was at the center of his work and did not look outward for critical approval or affirmation from the press. While Beckett did not devote much time to press and interviews, he would still sometimes personally meet the artists, scholars, and admirers who sought him out in the anonymous lobby of the Hotel PLM St. Jacques in Paris near his Montparnasse home.

I am reminded of a recent biography I read of playwright Samuel Beckett. Often looked upon as a recluse, or a cranky, withdrawn, curmudgeonly perfectionist, the biography allows us access to Beckett’s more personable, everyday self. His reputation as an unpleasant grouch is mostly rumor. The single most obvious quality of the man that emerges is the Beckett’s gentlemanliness. The same considerate and compassionate attitudes that Beckett demonstrated to both friends and strangers, I believe, are mirrored in the consideration and compassion that Beckett shows for the characters in his plays and books–indeed, for his attitude towards the world itself and its inhabitants of all backgrounds.

It goes without saying that the work itself must engage and be of good quality, but an artist can seriously hamstring his or herself by being a jerk-face in the real world. Gentlemanly attitude and comportment go a long way.

Jul 20, 2013

Being Part of the Cultural Community Means...

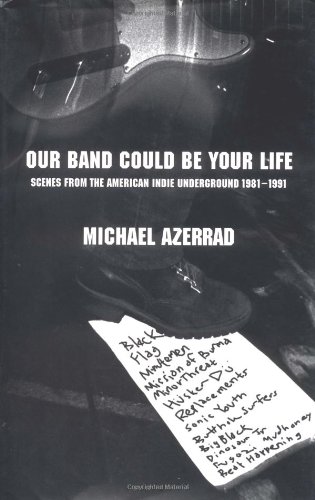

Austin Kleon has a recent post over on his excellent Tumblr that got me to thinking lately. The post is really a kind of book review of Michael Azerrad's Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground 1981-1991. In particular Kleon commentates on and outlines some quotes from the book such as:

Sonic Youth was especially good at networking — Thurston Moore published a fanzine in which he profiled bands and musicians he wanted to connect with, they would figure out who the hot critics were and go schmooze with them at parties, and they would do everything they could to help out other bands, building up tons of good will. A lot of this was calculated, of course, but it also just was a natural outgrowth of the band members’ interests and curiosities. Here’s Lee Ranaldo:

"We’re all voracious acquirers of information, whether it be books or movies or whatever, we’re just really vastly into what’s going on in culture and trying to synthesize what’s going on. I think that was just a natural impetus, a natural tendency…“A lot of bands are trying to present themselves as a singular entity in the center of it all. And I think we’ve always been the exact opposite, trying to present ourselves amidst a universe or a society of stuff going on.”

This makes me think of running a small theatre company. Being an indie theatre artist in a small theatre group is similar to being a musician in a small indie band. Ranaldo could be referring to how small theatre companies and the artists involved with them interact in the Dallas cultural landscape, and by extension, most large arts-intensive cities.

A community forms because we are all interested in each other as artists. We share interests and passions. In fact, in regards to how we relate with one another, I would argue the people are more important than the work they make in an arts community. After all, a community is people, not the work/products of the people.

A community forms because we are all interested in each other as artists. We share interests and passions. In fact, in regards to how we relate with one another, I would argue the people are more important than the work they make in an arts community. After all, a community is people, not the work/products of the people.

Here's how this works in a cultural landscape like Dallas. First off, there are around 50 or so theatres operating at any given time in the DFW area. Second, theatre-makers make horrible theatre-goers.

But just because we don't see each other's work very often doesn't mean we are out of touch with the community. In fact, it could be argued theatre artists support each other far more than they support each other's work.

That said, Ranaldo's last statement above of "a lot of bands think of themselves as a singular entity in the center of it all..." is a perennial problem in the indie theatre community as well. Usually it is a small group, newly formed, that comes along, trying to stand alone thinking, "We'll do it better..." without really even knowing what has happened before in the area. I think this explains why so many theatre companies start with Beckett or Sarah Kane (or now, Annie Baker).

The other way the singular entity problem shows up is when a the folks at a theatre think they are too big for those around them. They have either lasted longer (rare), had some recent minor success, or feel they are doing something far more important that what others are doing.

No one profits from the Singular Entity mentality.

Kleon's post about the book outlines more quotes that provide additional food-for-thought. I'll address them in upcoming posts.

Kleon's post about the book outlines more quotes that provide additional food-for-thought. I'll address them in upcoming posts.

Jul 17, 2013

A blast from the past...

So, back when I was an undergrad at that wild and desolate hotbed of creativity, the College of Santa Fe, I participated in a number of student films. Even though I was a theatre major, I took a bunch of film and video classes. I just found an old DVD of some of these old projects (one of the first DVDs someone burned for me... before that everything was on VHS). I was able to upload one of the student films I had acted in onto YouTube. I am pleased with my performance, even after all these years. Also, I am reminded that once, like we all were, I was young... and had hair...

Jul 14, 2013

Jul 10, 2013

Why Attempt a 380 Minute Solo Improv?

So I have decided to attempt a solo improvisation lasting 380 minutes, or nearly 6 and a half hours.

What possibly could have induced this insane idea in me?

A few things, actually...

It can, in theory, be done.

First, I performed 13 hours of improv as part of my friend Jeff Swearingen's attempt to raise money for Orphan Outreach. His event was called Whole Lotta Improv and was billed as a single-story 48 hour longform improv set. The press was told it was an attempt to break the Guinness Book of World Record for longest improv, but that was just a marketing point, since this sort of thing has been done before (see below). Besides, due to venue rental troubles, the event only lasted 30 hours, not 48. I performed 7 hours one night and six the next evening. There was a kind of rotating ensemble of many improvisers who subbed in and out. Many times the audience was non-existent and I doubt a great deal of funds were raised. I had fun, but also had mixed feelings about the event. The improv was extremely repetitive in places, but it showed me that a long story could be improvised at great length.

The good folks that are part of the improv community in Austin kind of regularly do really long improv shows. The Well-Hung Jury (later to become the Available Cupholders) tried to break the Guinness Book World Record for longest continual single-narrative longform improv years ago (27 hours, in 2000). Just recently, the Hideout sponsored the 44 Hour Improv Marathon. And even though, technically it was 44 one-hour shows back-to-back, the feat was still impressive since eight improvisers performed the whole thing the whole time.

Even including Swearingen's Whole Lotta Improv, Well Hung Jury's 27 hour feat and the Hideout's 44 Hour Marathon, I have never heard of anyone attempting a 6+ hour solo longform improv. If I can pull it off, I'll aim to make it a single continual narrative as well.

Also, I heard about Mike Daisey's 24 Hour monologue All The Hours In The Day just a short while after he did it. He performed it in a high school auditorium in Portland back in September 2011 at the TBA Festival. This was an amazing feat, even though he took a fifteen minute break every hour, sat at a desk the whole time and had prepared the whole thing beforehand. There's a good recounting of it HERE (with video). Here's my initial reactions to it HERE.

My main reason for wanting to attempt a 380 minute improv is because I am turning 38 years old in September. I have been in the theatre now for over 20 years, or half my life. As I get older I look around and wonder if I am where I wanted to be. I wonder where it is I wanted to be?

I have become hungry for some big thing to challenge me, to push me, to scare me. I have grown lazier and fatter and less capable of being astonished and I want to once again really feel... risk! Risk failure! Risk everything! Risk amazement! I want something to get behind and strive for. So, how about the impossible?!

Since doing a 45 minute set of Dribble Funk solo improv scares the crap out of me and pushes me to breathless physical and mental drain, a 380 minute set ought to dredge up whatever it is I'm made of. I will pit myself against myself, and then see what comes of it. Or totally fail in the attempt.

Either way, I'll be on stage, alone, for over 6 hours on Septmeber 1st, for the life of me, unwinding a made up story.

Details and such on DRIBBLE FUNK 380... HERE

Jul 8, 2013

Next Project... The Impossible!

With this post I am officially announcing my next project... Dribble Funk 380.

In September I will be turning 38 years of age. I have decided to do something impossible. I have decided to attempt a 380 minute solo improvisation. 380 minutes adds up to 6 hours and 20 minutes.

Yep, I will be alone on stage performing continuously for over six hours, completely making the whole thing up.

Let me be completely honest here: THE VERY THOUGHT OF THIS SCARES THE EVER-LOVIN' CRAP OUTTA ME!

Dribble Funk is a story-based solo improv format that I have been developing since 2005. It is the only kind of performance that still floods me with stage fright. I mean, butterflies in the stomach, the whole shebang.

That's the reason I keep doing it.

The longest set I've ever performed was just under an hour. So, honestly, I'm not even sure I can do a solo improv set for over 6 hours. As some may know, I am not the paragon of athletic fitness. This will take a serious amount of stamina, both mental and physical.

So, here's to the impossible!

Dribble Funk 380

September 1, 2013 starting at 6 PM

At the historic Margo Jones Theatre at Fair Park,

1121 First Ave., Dallas, TX 75210

Tickets: $10 suggested donation

Jul 7, 2013

Kristoffer Diaz's #freescenes: Charles Mee for the YouTube Age

I file this under the Why-The-Hell-Not? category. Because, seriously, it is a brilliant idea from a Pulitzer Prize-losing playwright. Excellent way to take advantage of internet technology, nurture a community and most of all for Mr. Diaz, workshop material.

Kristoffer Diaz describes his #freescenes experiment thus:

The more thorough telling of the backstory is here. The text of the scene is here.

Kristoffer Diaz describes his #freescenes experiment thus:

And so I thought what I’d do is give some scenes and monologues and maybe eventually a whole play away online, and hope that maybe some actors might want to play with them. And I hope that through the power of the internet, those actors can share some of that work with the world. And me.

So later today I’m going to post a scene here on my Tumblr. It’ll be the whole scene, stage directions and all. What I would love to have happen is that actors all over the world — here in NYC and in small towns nationwide, in other countries, in whatever translations and languages — go ahead and record themselves doing the scene. Think Charles Mee in the Youtube age. Do the scene. Put it on the internet. Tell me about it.Here's one of the ones posted online so far. Really sweet, well-acted scene, too.

The more thorough telling of the backstory is here. The text of the scene is here.

FUN GRIP at IFO 5

FUN GRIP IMPROV will be performing at the 5th Annual Improv Festival of Oklahoma on July 13, 2013, 8:45 PM. At the Sooner Theatre, 101 E. Main St. Norman, OK 73069. Tickets available at the door.

If you are in central Oklahoma next weekend, come on out.

Bike Soccer Jamboree Episode 21

That's right, BSJ, "the little podcast that could" has crossed the line of more than 20 episodes. In episode 21 Jeff Hernandez and I discuss summer plans, the heat if Texas and kayaking Aleutian cats...

Go have a listen.... HERE

Jul 6, 2013

Smaller Audiences, Better Audiences

Years ago, when I lived in New York City as a young actor, I was signed on to my first agency. This agency is the kind that represented those folks that dress as toy soldiers and stand outside the F.A.O. Schwartz Toy Store around Christmas time. They represented magicians. They represented leggy models who gestured towards rotating cars at automobile shows.

I learned a lot from that first agency. One important thing they told me was "people won't hire you if they don't know about you."

Skip ahead to closer to now...

I had a heated discussion over beers on the back patio of a bar recently with a good friend of mine. He was giving me semi-drunken and very unsolicited advice and, though he did not mean it in such a way, it initially came off patronizing. The advice was about how to get attention from the press at all costs in order to get the press to draw people to my shows. He advocated aggressively pursuing feature stories and profiles above all, even when you might not have anything to promote.

I agreed that features could be beneficial, but I differed in my belief that these sorts of things should necessarily be pursued. I especially drew offense that one should get press even if there was no reason to do so (i.e. nothing to promote). I also caused tension by stating that I don't believe that the press is the be-all-end-all for actually promoting one's work.

Related side-tangent: My modus operandi is one that could jokingly be described as "anti-promotion." I try not to go around shouting from the rooftops about how cool I am, where I've been or what I have accomplished. This is not to say I haven't done anything warranting potential boastfulness. It is just, I do not like that trait in others, so I do not propagate it in myself. I know it is a thin line to walk. As an artist I must promote my work, but so often I see lesser artists way over-hyping themselves. When I look them up, and see that there is way more flash than substance, I am usually let down by what I find. Instead of discovering the tip of the iceberg, I realize I have seen the submerged part first and there is very little left that is engaging. This over-hyping comes off as pretentious boasting. In my book, it is one of the worst things an artist can be... so full of themselves with absolutely no ability to back up what they claim they can do.

It should be noted, nine times out of ten, those folks who need to tell people how good they are, usually aren't.

I try to operate more like the people I admire. These people just do stuff, create stuff, relentlessly, and then let audiences discover what they have done gradually. That act of discovery is powerful.

The audience members, or patrons as I call them, come to the work all on their own, in their own time and in their own ways. Supporters of the work build over time, gradually, through word of mouth. I imagine, after a patron experiences a show of mine - maybe two - he or she will look me up online. If they like my stuff and what I stand for as an artist and person, they join my mailing list. They become advocates for me and my work. I have made a connection. Bluster and boastfulness can simply be a turn-off that works as an obstacle to this process.

Taking a for-instance from my own experience: a young improviser last year took one of my workshops. He got a follow-up email from me thanking him for taking the workshop. At the bottom of the email, as part of my signature, was a link to my website (this website). He clicked the link and then once here clicked to other things. The next time I saw this improviser he confessed that he was floored at how extensive my artistic pursuits were. He had had no idea that I had directed this and that, or worked with so and so, or performed at XYZ and so on. He confessed that during the workshop, though he found it really fun and beneficial, he just thought I was "some guy." The improviser asked me why I hadn't mentioned any of that to him before. I replied, "Would you have believed me and whatever I had to say about myself if you hadn't discovered this stuff on your own?" His exposure to me was way more personal and tremendously more powerful since he discovered the bulk of what he knows about me on his own. I became his discovery. He owns that discovery.

It is a powerful way to connect. And connection is what it is all about.

So, I don't really court the press. I don't ignore it, but I don't aggressively pursue it. I don't play that game. When I do stuff that warrants press, I reach out without getting in anyone's face. The press shows up or it doesn't. In the long run this may prove to be a fool's belief and I may well someday change my mind about it, but only time will tell.

"Be so good they can't ignore you."

~ Steve Martin

Plus, nowadays, with all sorts of avenues open for mediating information (outlets such as this very blog), the need for press is not as all-consuming. The artist has more control (well, marginally) of and the where-with-all to get the word out to prospective audience members.

The chief benefits I see from press are pretty basic: lead-ups and reviews do a little bit to generate buzz and online press serves as a nice timecapsule or archive of (what one person thought) of the work. And that's about it.

The chief benefits I see from press are pretty basic: lead-ups and reviews do a little bit to generate buzz and online press serves as a nice timecapsule or archive of (what one person thought) of the work. And that's about it.

As my friend was aggressively telling me how wrong I was not to flat out exploit the press as much as possible to get the word out about my projects, especially using feature write-ups, he said something like, "Don't you want to get as many people as possible to see your stuff?"

And to my surprise, without a pause, I replied, "No. I don't want as many people as possible to see my stuff!"

I was surprised because I had never said that out loud before. But it was true. To an extent.

Let me explain...

Ultimately, I want a great number of people to experience my art, especially my theatre work. But I'm in no hurry. I look at it as a long-term thing. I want word of mouth and build up. I want my hard-earned reputation to carry my work to bigger and bigger audiences over time, like a ripple in a pond. I want people to discover me. The people that see the work now will tell their friends and then those people will tell others and so on. It will take time, but the trade-off is a matter of quality, not quantity.

The early-adopters (so to speak) of my work have something that others don't: they saw it back when... There is an exclusivity to it. A value. The tide will rise, even if it has to happen slowly, and encompass more and more of the shore. My relationship with these individual audience members, these patrons, will deepen, too. They will progress along with me. I will grow and the community will pick up more and more as we go along.

Sirens of yore didn't yell, they sang. They lured. They seduced. I prefer to hum my own little song, not shout as loud as possible, "Hey, I'm here, pay attention to me!"

It is a matter of perceived value. I'm making high quality, small-scale theatre. It is somewhat exclusive.

So, I'll take a really engaged 20 audience members over a disinterested 100 any day of the week. I don't just want butts-in-seats, I want advocates. I know this flies in the face of the usual assumptions, but I am not interested in the usual assumptions.

My friend followed up, though, with a very good suggestion. He asked, "Wouldn't the percentages of people that could be really into your works be higher if the amount of people who were exposed to you in the first place was higher?"

He had a point. The more people who know about me the better the chances of gathering the small number of quality audience members. The more quality audience members I have now, the more that number can grow. Thus, features and profiles from the press are a good idea. I know this. I'm just not convinced I should court them like a love-sick prep-schooler. But if and when they come my way (because I can no longer be ignored), I will embrace them.

After all, if you are doing it right, you don't find an audience for your work... they find you.

Jul 4, 2013

Fun Grip at the Margo Jones Theatre

Untitled, a photo by dribblefunk on Flickr.

Jul 3, 2013

Aaron Loeb on Criticism

|

| Playwright Aaron Loeb |

Here's an excerpt:

The other way we say “I don’t give a fuck. Go fuck yourself.” when offering criticism is, “I’m just being honest.” Or “I’m just calling it like I see it.” It offers the recipient of the critique absolutely no purchase. “Look, it just didn’t work for me. That’s just how I see it.” There is nothing for a creative person to do with that other than feel bad or determine you’re an asshole (likely the former, since creative people will generally seize upon any excuse to feel bad).He follows with an alternative way to offer criticism, which he calls the "assumed master" approach:

You assume the person sharing is a master at their craft and you try to backtrack to find the reason why you didn’t understand — what clever trick was the master pulling? Your critique can be, simply, talking through your thought process. In hearing you describe what you heard, “the master” will likely learn something about her work AND be encouraged to do more of it. And when you get stuck — you just can’t work out why the master did something — well, she may find that helpful too.I think this is a remarkably beneficial way to approach criticism and I have found myself doing it from time to time to young actors and playwrights without even knowing it. Out of diplomacy I have purposely given the person much more credit than I think they rightly deserve, and it almost always gets past any reflexive defenses. Believing they sorta got away with something or that I really am a dolt, they actually listen as I describe what I noticed, what I didn't understand, and so on. If I use as a director on actors they also listen ("Oh, I see what you're doing there. You've given me an idea..." and so on). I, the receiver, seemingly take all the responsibility. The creator is free from fault since whatever is in the work is reasoned to have been purposely placed there by the "master."

In a related way, I wonder what would come of "professional" press criticism if the reviewers and critics genuinely approached any piece like it was already an established Beckett or Shakespeare play. That any short-comings were at their end, not at the creator's end. Even if it was just a pretense, I wonder... What would the criticism look like? If the basic, foundational assumption was always that they were dealing with a "master" of the artform, instead of coming at it as " well, good try for a beginner..." (or worse, "emerging artist"). How would the criticism itself come acrtoss? What would this different perspective demand of the artists doing the work? How would they approach the creation of the pieces if they knew they would be assumed to be a "master" of their craft?

I'm not advocating a change to press criticism in any real way (it is what it is), but Loeb's essay does make some tasty food-for-thought...

The original article is at Medium.com... HERE.

Jul 2, 2013

On the Purpose of Small Theatres

On a podcast a few years ago I listened as a local critic explained that she thought the purpose of smaller theatre companies in the cultural landscape was simply to be a training ground for the larger stages in town. She was referring specifically to Dallas. In her view, that was the explicit purpose of the small, homeless companies with small budgets... to be a practice field until actors, directors, designers, playwrights and so on could move up to do the real work on much more legitimate, mid-level and larger stages.

I remember being very dismayed at this attitude, especially coming from a critic in town.

Recently, Stephen Foglia over at the Undermain blog posted an excellent essay/follow-up to a recent panel discussion at the 2013 TCG National Conference. TCG13 was held in Dallas at the beginning of June and one of the panels entitled “Living The Margo Jones Legacy: Breaking The Habit Of New Play Development”, aimed to challenge current orthodoxies (including those unacknowledged) in the development and production of new plays.

Foglia traces through one thread of the panel conversation:

Jason Loewith, Artistic Director of the Olney Theatre Center (also former Executive Director of the National New Play Network and a writer/director himself), drew an image of the playwright’s progress through the national theatre landscape. Theatres, he said, of different sizes, occupy different levels of the environment, and small theatres find young playwrights on the ground floor, pass them up to mid-size theatres in the understory, who then pass the playwrights up to the LORT theatres representing the canopy or emergent layer. His metaphor approximated the layers of a rain forest and nicely captures the living web of competition new plays must operate in.Foglia points out that the twist in the metaphor is that unlike animals in a rain forest, playwrights can occupy many strata at the same time. He cites contemporary playwright du jour, Annie Baker as an example:

...to choose a new playwright, Annie Baker is more or less bestriding the world right now, with Obies, and commissions, awards, productions at Soho Rep and Playwrights Horizons casting spores that germinate in mid-size regional theatres all across the country. But all the same The Aliens will continue to be produced by small companies, ad-hoc collectives of homeless theatre-makers, and many others on the forest floor.I don't necessarily disagree that, yes, this is how the greater new play system sort of operates in the American Theatre, but I do draw issue to phrases like "small companies, ad-hoc collectives of homeless theatre-makers, and many others on the forest floor."

When is it that the word small must equal lesser?

I recently posted an essay on the ATL blog, Notes From The Lab, entitled "On Assumptions, Plays and Hibernating." In a nutshell I pick apart some common assumptions about what theatres, particularly a small theatre like the one I am a part of, Audacity Theatre Lab, are suppose to do and how they are suppose to do them.

In my gut, I believe small can mean fast, nimble, entrepreneurial. I believe small might be one key to the future of theatre. I believe small might be hugely important.

In another essay I posted on the ATL Blog, entitled "Part of the Cultural Landscape" I flipped the metaphor that Foglia lays out above. In my opinion the diversity of the theatre scene (or rain forest ecosystem, to push the analogy) is that the larger, more institutional theatres in a region actually serve the smaller companies.

Let me quote from myself:

It is with this in mind I run a small garage band-size theatre based in Dallas called Audacity Theatre Lab. Both the size and location are conscious choices. We affectionately call ourselves indie. With no permanent venue to call home we are urban gypsies (instead of the term homeless). We operate with an extremely low overhead. We have no “season,” but instead present work when it is organically created. We do work at festivals and venues around the country as well as locally. We operate as a collective and give the artists involved total control of the projects from idea to finally putting photos in a scrapbook long after the production has ended. We do theatre because we, as artists, have something to say.

This is possible because of the wonderful diversity of the cultural landscape in Dallas. Audacity can operate far down the Long Tail and fill its particular niche because there are companies such as Dallas Theater Center, Undermain, Kitchen Dog and other TCG Theatres doing a lot of the heavy lifting. With these groups acting as the core, groups like Audacity can happen on the fringes. We can explore and experiment and advance the art form in very particular ways. As independent artists and groups we are freer and should take full advantage of that. That is how we are part of the cultural ecosystem.Foglia goes on to note how theatres choose plays and, more interesting to myself, how smaller groups can clog the growth of new plays and ideas:

The majority of companies do not select plays for their newness. The majority of companies want to do good work that they love, that fits their style, and that will draw in audiences. They’re going to grab plays by successful artists. Successful plays. The same ones, for the most part, that everyone else loves. And the more they produce plays that are already successful, the less they operate as a feeding system, passing new playwrights on to the majors.

There’s a related inverse example as well. Many small companies produce work internally. They may have writers in their company, or they may develop work as an ensemble, but they may ultimately be islands unto themselves. They neither draw successful work in, nor pass their own successes out.That last paragraph is chilling in its implications. As a theatre creator in a small, bootstrapping organization, the urge often really is to hunker down and be an island, to isolate ones self, to create a small bubble for working and guard against outside interference. In and of itself, I do not have a judgement call on whether that is right or wrong. Ethically speaking, sometimes these companies as "islands unto themselves" only accomplish productive work because of the isolation. And there is not a necessity to share. Sharing is voluntary.

My personal thoughts differ from the greater ethical ramifications. Though isolationism has validity, I'm interested in serving the art form itself. In order for the field as a whole to profit and grow, these small, internally produced explorations must be disseminated to the wider cultural landscape. It can be a trap, yes, but not one that must be fallen into.

Do I believe smaller, independent companies have something to offer the greater theatre community? Yes. Do I think their role is lesser, say, than larger institutions? No. The field is broad and diverse. That very diversity allows for many players to play many roles. Small theatres merely hold a certain place in the cultural landscape.

Make new, awesome work. Share it. Everything fits together.

A debriefing of DINOSAUR AND ROBOT STOP A TRAIN

|

| DINOSAUR AND ROBOT STOP A TRAIN in performance |

It has been about a week since my original show DINOSAUR AND ROBOT STOP A TRAIN closed at the 15th Annual Festival of Independent Theatres. It turned out to be a pretty successful affair. Overall good reviews, good audience feedback, and, on the whole, I was relatively pleased with it as well (it should be noted that I am very very seldom happy with anything I'm involved in. I am my own harshest critic).

I have created a Flickr set of photos covering a lot of the process of the play through rehearsals and costume construction. That can be viewed HERE.

There have been some nice write ups and reviews, all of which have been collected on the ATL blog, Notes from the Lab. Check them out HERE.

There is also a page on this website, especially if you are interested in producing the piece at your own theatre somewhere outside of Dallas. Just contact me. Meanwhile go HERE.

Lastly, my personal thoughts and feelings on creating a completely original piece of theatre from scratch and what it was like to write, market, produce, direct, design and perform in it. Those thoughts can be found HERE.

As for the future, I plan to submit the piece to at least a few festivals and maybe mount it again here in Dallas next year for a proper run before I completely hand it off to the world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)